Welcome Home to East Africa, Part 2

Edition 33: Maasai Mara National Reserve, Nairobi and the Berlinale

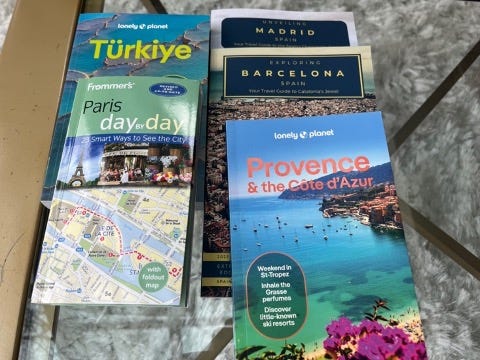

I’ve been happily ensconced at home the past three months, although as piles of new travel magazines and guides build on the coffee table, it’s clear I’m dreaming about the open road again.

In ten days, I’ll head to Berlin for the European Film Market and Berlin Film Festival, taking meetings on my TV projects. Work, not vacation, but still, my first time back in many years, and Berlin is such a creative, vibrant city that I’m excited. Late March will see me warming up in Exuma for a few days. And April brings a holiday in Paris and Provence to celebrate my birthday. 🥳🎁🇫🇷

But first, travel back with me in time to last October when I visited East Africa – a trip I still think about frequently. Today our stops are the Maasai Mara National Reserve and Nairobi.

Leaving Tanzania and arriving in Kenya was not straightforward. Large storms in mid-2024 sidelined the main road between the Northern Serengeti and Kenya and the alternative route was clogged with transport truck and long border delays.

Instead, we boarded three smallish planes to stamp our passports out of Tanzania, then into Kenya, then finally on to the Maasi Mara National Reserve. (In the language Maa, Mara means spotted, so the spotted land of the Maasai.)

I’m a claustrophobe so small is never better for me. But it was a glorious clear day, and we flew along Lake Victoria, the world’s largest tropical lake. Bordered by Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda, Lake Victoria is home to fish, mammals and reptiles found nowhere else in the world.

The lake is a critical part of the East African economy, providing transportation routes, hydropower, more than 3 million jobs and food for 40 million people. Yet, it has experienced deterioration due to unregulated exploitation, invasive species, habitat degradation and pollution. Inconsistent rainfall pattens in recent years – too little rain then too heavy causing floods – is disrupting ecosystems and forcing community relocations.

A pattern felt the world over as the climate changes, including of course Los Angeles with its cycle of drought and mud slides brought on by sudden heavy rain. Such a relief to see the fires are finally fully contained.)

Maasai Mara National Reserve

Located in Kenya’s southwest, this amazing nature reserve covers 583 square miles and is abundantly rich in wildlife and birds. We stayed with @beyond, an ecotourism travel company with 29 lodges, camps and yurts in Africa, Asia and South America.

Kichwa Tembo Tented Camp, their permanent tented camp, sits on a private concession on the western border of the reserve. Access to the concession allowed for bush walks, night drives and bush dining, although our long game drives (10-12 hours a day) took us both across the concession and across the whole reserve.

The concentration of animals in the Maasi Mara is stunning. The elephants made me cry every time I saw them. Their eyes are so knowing, and aware, and kind. They are an extraordinary species; long-living (into their 80s), intensely loyal, and with a remarkable memory.

The Sheldrick Wildlife Trust who runs the first and most successful elephant orphan rescue and rehabilitation program in the world, spends up to 10 years re-integrating elephants and rhinos back into the wilderness after saving them and nursing them back to health.

Gamekeepers say a re-integrated elephant will travel hundreds of miles back to the centre to introduce their babies to the gamekeepers who once saved their life, or to give birth there. They do this every single time they have a calf, bringing the entire herd of female relatives and any young male offspring.

(Around age 12-15, male elephants undergo ‘musth’ which results in high testosterone levels and aggressive behaviour. They’re kicked out of the herd to make their own way and ensure continuation of the specials. It’s sad to see a young male following in an attempt to get re-admitted only to be rejected by the matriarch.) Single male elephants can form a ‘coalition’– sometimes called a bachelor herd – and travel together until one of them meets a female to mate with.

This pattern happens with many of the animal species, including lions who are eventually challenged by another male and kicked out of the pride. Because they have no hunting skills – hunting is done by the females – they grow weaker and weaker and eventually become prey themselves.)

Although we’d already seen so many animals in Tanzania, including the Big Five, Kenya brought some special treats. This included large rafts of hippos who manage to maintain their 3,000lb figures eating vegetation.

Adorable, yes? Except they kill more Africans than any other animal. More than lions. More than hyenas (who rip their prey apart without having the courtesy to kill them first, then eat until they gorge, vomiting if they need to create space to finish the smorgasbord). And more than cape buffalo who are the only animal who kills without reason or provocation.

Hippos go grazing in early morning, they’re aggressive (no gentle giants there) and they run at a fair clip (30km/h over short distances) rampaging through villages and trampling people to death.

They resemble pigs or warthogs, but in fact their closest living relative are cetaceans (whales, dolphins, porpoises) from whom they diverged about 55 million years ago. And indeed, while we had a bush lunch on the edge of the river (hoping against hope the cliff face was secure), they spent the sunny mid-day swimming, shitting, fighting and making new babies.)

In Kenya, we also saw the endangered cheetah. Unlike other cats, the cheetah cannot climb trees which makes them easy prey, despite being the fastest land animal on earth over short distances (120km/h in 3 seconds). During one game-drive, the call came on the radio that a cheetah mom and her cubs had been spotted. That she had managed to bring all four cubs to the cusp of adulthood is remarkably rare.

We strapped in as our jeep set off in pursuit, cameras at the ready, for the 90-minute drive it would take us to reach the rendezvous point.

The Maasi Mara and the Serengeti share the same ecosystem and the artificial nature of borders is clear when you stand at the intersection point of Kenya and Tanzania. Most of the time you see very few other vehicles. (At least in the Northern Serengeti where we were; our guides said the mid-Serengeti is much more crowded.)

But in a rare spotting like a cheetah or a black rhino, all the guides radio to each other and the jeeps descend.

Suddenly it’s Bread and Circuses time, as the drivers try to outmanoeuvre each other for the best position to watch the cheetah takes its kill. (I became a butt of jokes on the trip as I wouldn’t watch a kill. Yes, of course, it’s cycle of life, but why would I want to be a voyeur of death? I’m a vegetarian for a reason.)

There are strict rules against going off track. Most drivers obey them, but there’s always some cowboy that wants to prove themselves or make their passengers happy. Interestingly, the Sheldrick Trust donates the game warden trucks who intervene to protect the animals.

Unlike the Tanzanian mobile camp I wrote about in my last newsletter which packs up and follows the Great Migration throughout the year, &Beyond is a permanent camp. Fences keep out the biggest of prey. But there are animals that live inside the camp, including warthogs whom I’m telling you, look fierce enough when they’re charging at you to keep you away from their children on the path.

I was SO sad to leave camp on our final day. The Kenyans took such good care of us. Extraordinary food, singing and laughing and talking – whether that was with the head chef as we toured his vegetable gardens. With the guides learning about ecology and conversation. With the Maasai medicine man learning how many ways an acacia tree can heal you.

Reading the suggested books to learn about the history and culture. (Welcome, new subscribers! The book/movie list is in Part 1, Welcome Home to East Africa.)

But there was still one more adventure to look forward to we ran out of trip.

Nairobi.

It was such a shock to arrive in a city after twelve days on safari. The animals were still there – herds of cows moving along the side of highways, giant herons and hadada ibis in the tree, the extraordinary Nairobi National Park with its big game in the middle of the city.

But suddenly there were the two-legged variety, as well.

Nairobi’s a modern, global city of approximately 5million. The extremes of poverty and wealth are on full display, from broken down buses being pushed along the streets to the Kibera slum to mansions under armed guard in the suburbs of Karen and Lang’ata where the political and business elites (and many working for international aid agencies) live.

Terrorism continues to be a threat in Nairobi, primarily from communal militias or Al-Shabaab (based in Somalia, which borders Kenya to the north/east).

We stayed at the Fairmont Norfolk; the hotel is behind barbed wire and every vehicle that goes in/out is checked for bombs. (The hotel itself was bombed in 1980, widely assumed by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, although they denied it.)

Walking in the city is discouraged for tourists. We went on excursions every day and encountered no problems. We loved the energy of the city and its people, but we were always escorted by a driver who the hotel arranged. This included for meals, to visit the elephant orphanage and the centre, the Karen Blixen house at the foot of the Ngong Hills, arts and cultural tours including museums, etc.

Security is high most places you go, in particular at shopping centres, given the deadly Westgate shopping mall attack in 2013. Although most terrorist attacks the past few years happen closer to the Kenyan-Somali border.

Last year also saw youth-led civil unrest during which several protestors were killed or disappeared. Tensions simmer due to the high cost of living, corruption, and attempts to stifle dissent. Kenya is producing highly educated youth (it has the best system on the continent) yet the job prospects are bleak and often means leaving the country and their families behind.

Kobe Tough.

An amazing social initiative we visited was Kobe Tough. Originally, it started as a direct response to the effects of climate change among the Maasai, pastoralists who move with their cattle. Prolonged drought were wiping out entire herds of cattle, and the economic devastation forced early marriage on daughters. (Dowry is paid in cows.)

The group has already begun working with Maasai women to upskill their traditional beading into luxury goods to be sold. (Think Apple watch bands and gorgeous belts, along with jewellery). Then Covid hit and tourism plunged, and 300+ women, mostly single mothers, orphans and widows who had been working making ceramic beads in Nairobi, were laid off.

Kobe Tough stepped in, providing not just employment but often housing as well. It’s truly a success story of community. They ship throughout the world, and everything you buy goes to support these women.

A midnight flight of Nairobi connecting though Paris on Air France’s new Airbus 350-900 series planes (burns 25% less fuel than older planes and has a 40% reduced noise footprint) and suddenly we were back in Toronto.

The elephants and zebras and cheetahs replaced by squirrels, chipmunks and raccoons. As much as I like the furry little guys, it just wasn’t the same. (Mind you, I didn’t have to hide my throat from them, unlike Mr Hyena.)

Ashe Naleng Naleng pii – thank you very very much for joining me for this thirty-third edition of Letterbox!

Next Letterbox: the Berlinale, seven-four years old, one of the largest and most important film festivals in the world, and certainly one of the most political. Originally created at the beginning of the cold war, to showcase the free world to the Berlin public and beyond.

An aim as topical as ever, as we watch leaders and others who ought to know better flirt with fascist tendencies. Purges and witch hunts are seemingly the rage again, as if these ‘leaders’ invented them instead of just borrowing the same old, sad copybook of the past.

The European Film Market, held in conjunction, sees 10,000 industry folk come together to do business. It’s the first major film market of the year, and the most important one for global co-productions, which is increasingly important in this age of contraction in the TV and film markets. But I’ll save all that for the next newsletter! See you then.