It’s a scurrying time of year.

Work that presses to be completed despite the holidays. Writing deadlines. The tantalizing lure of books to read and movies to watch. And of course Christmas.

Underlying it all – a profound gratitude as the house fills with family and friends, dinner parties and holiday celebrations, big and small.

The memory of those who left too soon is much on the mind. I’m conscious, too, of those for whom this time of year brings loneliness or a stark reminder of the struggle for survival. Whether that’s because of wars which rage around the world, or the shameful inequity our own society allows to flourish.

The rumination about connection brings me back to my trip to East Africa.

Tobong'u Lorre –- Welcome Home, the border agents say when you stamp into Kenya. It’s how the hotel greets you for the first time, and indeed it’s something you hear over and over again. Such a beautiful sentiment, even for those who have no historic connection to the country.

Because don’t we all spend our lives seeking to (re)create a sense of home, with its illusion of safety and permanence?

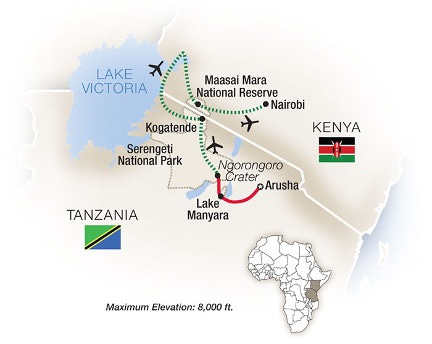

This autumn, I fulfilled a lifelong dream to go on safari. The trip with family and friends started with a few days in Kilimanjaro and ended with several days in Nairobi.

But the bulk of the trip was spent in open-sided jeeps on 10–12-hour game drives, trying to maintain eye contact with a lioness as she saunters within a few feet (breaking gaze = not good). Squatting behind a bush to use the toilet and hoping a buffalo doesn’t come charging. Eating stunningly good food at bush lunches or tented dinners, prepared by first-class local chefs for our group of fourteen.

Falling into bed every night, exhausted and hoping not to be attacked by the pack of hyenas who’ve set up shop on the edges of our mobile camp. (Mobile camp = no fences. Guns are banned in almost all of Tanzania so camp staff make do with sticks and animal calls to keep predators away in the dark.)

All in all – heaven. A truly transformational trip to a part of the world I’d never visited before and can’t wait to return to. And while my year of excited planning of the trip focussed mostly on the animals because I’m such a fanatic about the natural world, it’s the generous heart, kindness and joie de vivre of the people that I miss most.

Ngorongoro Crater and the Maasai (Tanzania)

Our safari started in the Ngorongoro Crater, the biggest intact volcanic caldera on Earth, and home to 25,000 animals. Due to its enclosed nature – you circle up and up in shroud-covered montane forest until you reach the rim and then drive over and down 2000 feet into it – this world wonder has effectively formed its own ecosystem so complete the animals don’t need to leave.

The crater is large (330 km²). You explore grasslands, wetland and woodlands and the vast array of animals for whom they are home: gazelles, wildebeest, zebras, cape buffalo, elephants, hippos, black rhinos, ostriches, and more, and so many birds.

I loved the symbiosis. Zebras and wildebeests roam together because one sees predators in the distance and one hears them. Birds catch rides on the backs of animals and help out by eating the insects and ticks. Female ostriches are bland-coloured so they blend into the grass during the day, guarding the offspring, while males have black feathers so they can take their turn at night.

Enroute to the Ngorongoro area, we spent several hours in a Maasai village taking a medicine walk, visiting a local school supported by Tauck (our tour operator), visiting with the women and girls (their culture is polygamous and multi-generational) and buying their beaded jewellery, and having lunch. It was an eye opener.

There are approximately eight million Maasai in the world, with the majority living in Tanzania. Traditionally, they are pastoralists (nomadic, moving with their herds of cows). The Maasai are not one of Tanzania’s largest tribes, but they are important, in large part because they maintain a traditional way of life.

In 1959, the British colonial government established the Ngorongo Conservation Area, to create a permanent homeland for the people who live in and around the crater, the vast majority of who are Maasai herders. (In 1951, when the Serengeti National Park was established all the Maasai locals were relocated to the NCA.)

The Maasai don’t hunt, our guides explained, thus are trusted not to poach the wildlife and to live in harmony with the crater’s ecosystem.

However, In 2021, the Tanzanian government devised a plan to relocate about 82,000 Maasai by 2027. NGOs such as Human Rights Watch decry the decision and the methods used, which they claim include scaling down essential infrastructure like education and health services, as well as access to pasture, water and cultural sites, and restricting movement in/out the crater.

The decision has been very controversial. Criticism of it is met with stiff retaliation, including media censure.

The government argues that the Maasai’s population size makes it difficult to maintain Ngorongoro’s pristine nature and safeguard its UNESCO World Heritage Site designation. Which of course ladders up to to tourism.

The impact of one’s visit to Tanzania is something I thought a lot about while there. There’s been much published in recent years about the environmental and cultural impact of tourism. Yet, tourism dollars is what keeps these national parks going and funds conservation efforts in a country where only 30% of people have full-time employment.

Dan Friedkin, who owns Legendary Expeditions, including Songa Migrational Camp where we stayed in the Serengeti, leases four million acres in different parts of Tanzania. He’s an automotive billionaire from Texas turned film producer, who spends more than $1,000 an hour keeping Tanzania’s only two anti-poaching helicopters in the air.

I was originally drawn to visit the country after watching a documentary about Samia Suluhu Hassan, Tanzania’s first female and first Muslim president. (Tanzania has 60 million people; it’s roughly 63% Christian, 34% Muslim, plus other faiths.)

Suluhu was elected as Vice President in 2015. She became president when her predecessor, John Magufuli, passed away in 2021 (a covid denier, he’s rumoured to have died of the disease). As president, she’s implemented many democratic reforms (although is not above media intimidation), expanded infrastructure, globalized the economy through investment and promoted tourism.

The UN estimates that tourism represents about 17% of the overall Tanzanian economy, and provides the country’s third-largest largest source of employment by directing employing over 850,000 people.

Tauck runs about 100 tours a year in Africa, thus are able to offer full-time employment. The guides we had in both Tanzania and Kenya were extraordinary. Their knowledge of, and commitment to, conservation and the natural world was deeply impressive (they’d all studied it at university and regularly go on refresher courses). I so appreciated the opportunity to learn from them.

You become attached, spending all day in the Jeep and over drinks in the evening, talking about life and family and Africa. Their love of country, in particular in Tanzania, is inspirational. ‘Please come back,’ they said at the goodbye, all of us teary-eyed. ‘Tell all your friends to come, too. The future of the Serengeti depends on it.’

The Serengeti and The Great Migration

The Serengeti looms large in the imagination even before you visit, because of references in poetry, music and film. The region includes approximately 30,000 km² of land, including the Serengeti National Park and several game reserves.

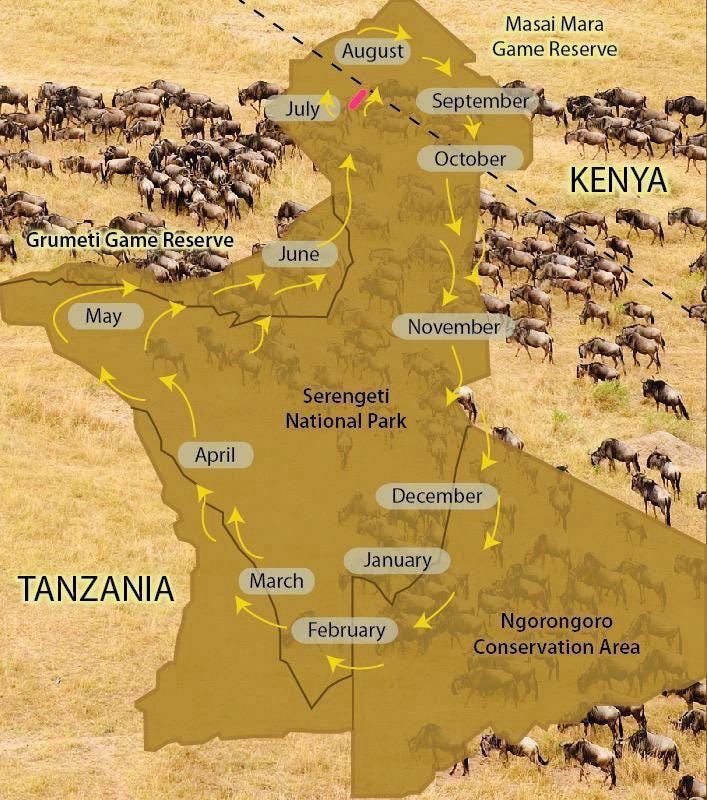

The Great Migration, an 800km trek of more than 2 million wildebeests (with zebras and gazelles), is the largest mammal migration on earth. Its timing coincides with the greening of the grasses during wet season, a time when animals can easily spot predators, which makes it ideal for giving birth.

However, as the plains dry, the wildebeest are forced to move looking for greener pastures and thus begin a clockwise movement cycle throughout the year, which includes the famous crossing of the Mara River.

We spent five hours parked in the hot sun waiting for a crossing. This cartoon captures the stop/start nature of the wildebeest as it considers whether to risk the alligator-infested river, often egged on by the zebras who also want to cross, but not to be first.

The days are long in the Serengeti. Breakfast starts at 5:45am, wheels up at 6:30am, and you return to camp in early evening. The roads are very bumpy – all the better to slow down the night poachers – and dusty. The days are hot.

From extraordinary sunsets and sunrises, to honey colored plains, to the genuine warmth and welcome of the people, it humbles you to know you’re one tiny visiting fleck in a world so different from our frenzied, consumeristic one.

And then of course there’s the animals. The Serengeti is home to the Big Five – lion, elephant, cape buffalo, leopard and rhinoceros. As well as hippos, ostriches, zebras, wildebeests, baboons, impalas, topi, gazelles, hyenas, warthogs, and the endangered cheetah. And so many more.

We saw them all, often right up close as they walked by our open-sided Jeeps. In the Serengeti, the guides drive off path, bringing you as close as it’s safely possible for you and the animals.

Of all the places we visited, the Serengeti (Africa’s oldest ecology) was my favourite. The vast open expanse means you don’t encounter other vehicles, except in a rare spotting like a family of cheetah, when the guides all radio each other and suddenly it’s bread and circus time as jeeps jockey for position.

During the day you race round gazing at wonder at the stunning acacia trees, the 500 different bird species, the 2 million+ animals doing their thing. You return to camp at sunset, where the staff meet you with hot facecloths to wipe away the deep red dust on your face and hands, and together you sing the Kenya pop song Jamba Bwana.

Tucked up into your bed at night with a hot water bottle, you wonder what animal is rustling those leaves as it passes by your tent, feeling both a little scared and deeply connected to the ecology around you. Then you wake, and go out to meet the day all over again.

Asante sana, Tanzania 🇹🇿. I hope to return one day soon.

Ashe Naleng Naleng pii – thank you very very much for joining me for this thirty-second edition of Letterbox!

Until next time, my friends, when I’ll write about the Maasai Mara Nature Reserve in Kenya, as well as our time in Nairobi.

But first, some African book recommendations from our guide Leah:

A Grain of Wheat by Ngugi wa Thiong'o (novel set on the threshold of independence).

The White Maasai by Corinne Hofmann – both a book and a movie (non-fiction about a European woman who meets and marries a Maasai man).

The Worlds of a Maasai Warrior: An Autobiography by Tepilit Ole Saitoti.

White Mischief by James Fox (non-fiction about a murder scandal from the 1940s British colonial times in Kenya).

Green City in the Sun by Barbara Wood (Historical fiction about two families over three generations in Kenya related to colonialism and interactions with local tribes).

Unbowed: A Memoir by Wangari Maathai

Whatever You Do, Don’t Run by Peter Allison (true stories from a safari guide).

I Dreamed of Africa by Kuki Gallman (also a movie).

West with the Night by Beryl Markem.

Barefoot over the Serengeti by David Read.

Here are hosts at &Beyond camp in the Masaai Mara singing Hakuna Matata (no trouble) to say goodbye. See you next time!

Helen - Wonderful column about your experience on safari. It brought back my own time in the Serengetti and the Maasa Mari,a long time ago as a young journalist. (I flew there on the Concorde! )But nothing matches the experience of seeing those animals in their home. And the skies. Thank you for stirring those memories, and I look forward to the next column

What a wonderful experience, Helen. Thank you for sharing it.