I love organized tours when I travel, particularly of art galleries, museums, and historical sites. Not all tours are created equal, but if you research you can find tour guides with advanced degrees in history or art history, who truly deepen the experience of a place.

In June, I took two outstanding walking tours in Rome. The first of the Jewish Ghetto including the Great Synagogue and Museum, and the second of The Colosseum, The Forum and Palatine Hill.

The history of the two intertwine, of course.

The Jewish community in Rome is the oldest in the world with a continuous existence outside of the Middle East. Roman Jews first came from the Holy Land in second century BC, and lived in relative peace at first as both Julius Caesar and Augustus supported laws that allowed them to worship as they chose.

In 1st AD, the Romans sacked the Second Temple in Jerusalem, stealing the gold to build the Colosseum.

A cheery place, the Colosseum back in the day. People bought tickets to watch animals from Asia and Africa tear each other to shreds in the morning, plus some early Christians they threw into the mix. Then it was time for public executions over lunch, followed by the gladiators fighting each other to the death in the afternoon.

The Coliseum was a private business, with food concessions for spectators to enjoy and branded goods to be bought while animals and the poor fought for their lives.

The gladiators were slaves owned by the wealthy including the political elite, who paid for their training and lodging. More than 1000 gladiators were killed each year, for more than 500 years, meaning more than a half million men were sacrificed for the entertainment of others.

We’re a blood-soaked lot, humankind. It’s nothing new.

Micaela Pavoncello was my Jewish Ghetto tour leader. Her father’s family came to Rome in Caesar’s time, and her mother is Libyan Jewish. The Roman Jewish are historically neither Ashkenazi or Sephardic (distinctions that came after the establishment of their community) but of course they expanded as forced expulsions drove Jews of different backgrounds to Rome.

(From Spain and Portugal in the 1490s, from the nation states of what is now Southern Italy in the 17th Century, from Arab lands after the UN establishment of Israel in 1948 and especially after the 1967 Six-Day War.)

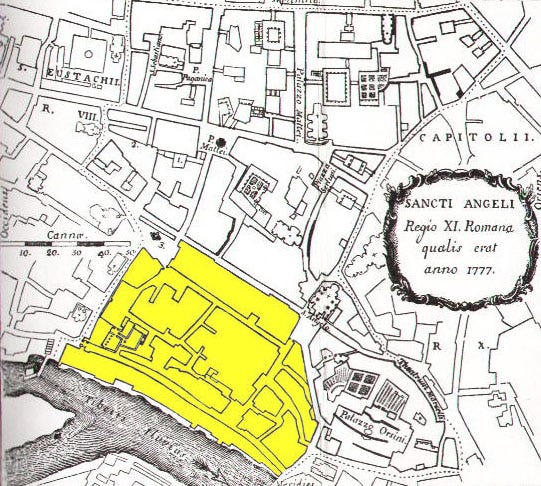

The Jewish Ghetto was established by papal decree in 1555. It required the 2,000 Jews who had called the city home since before Christian times to live in a walled quarter next to a river which constantly flooded and close to the fish markets that stank.

Jews were restricted from owning property, practicing medicine on Christians or having jobs other than money lending or selling clothing. They were forced to wear a yellow cloth on their clothes (Hitler wasn’t an original thinker) and taxed yearly for the pleasure.

The Catholic Church tried both a carrot and stick approach to convert Jews to Christianity. The perimeter of the ghetto is lined with churches (some with Hebrew on the outside) and attendance at Mass was compulsory. Jews would wear wax in their ears to drown out the sermons, sometimes falling asleep and getting whacked by the priest to wake them up.

(Roman mothers, both Jewish and Catholic, have a habit of raising their hands and saying, I’ll wake you up, in a modern-day reference to the slap.)

The Catholic Church lost control of Rome in the the 1870 unification of Italy. With this dramatic change in governments, the requirement that Jews live in the ghetto came to an end. But the centuries of crowds, restrictions, and disease had taken their toll and the population had shrunk in half. In 1888, the ghetto walls were taken down, and much of the area was demolished.

In 1904, the Great Synagogue of Rome was built (replacing five small synagogues erected to house different Jewish faith groups as they assimilated into the ghetto over the centuries), and a number of apartment buildings erected. Streets were widened and river embankments created to prevent flooding and reduce the spread of disease.

The ghetto is now one of the most desirable – and expensive – neighbourhoods in Rome. It’s a mix of Jews wealthy enough to buy their way back in, those too poor to have left, and the culturati and intelligentsia of all backgrounds and faiths who have found a dynamic community there.

Of course, Roman Jews did not fare well during WW2. They were told by the Germans they could buy escape deportation for an outrageous amount of gold. The Roman Jewish community was never rich, but they gave up their wedding rings and personal effects to be melted down and handed over.

The Vatican’s only contribution? A vague offer to lend them gold (with interest) if they could not come up with the needed tithe to save the women and children. Of course, the Nazis reneged on their promise. Twenty days before the end of the occupation, 25% of the Jewish population (more than 2,000 people) were deported to the camps. Only 102 survived.

Now numbering 35,000, the Rome Jewish community has 18 synagogues, their own Jewish-Roman dialect, musical and culinary traditions. As Michaela says, they’ve witnessed the grandeur of the Roman Empire, and its fall, the beginning of Christianity, the Barbarians, the Inquisition, The Popes, the ghettos, and the finally emancipation, before World War Two and the Shoah (Holocaust).

I originally became interested in the Jewish history of Rome after subscribing to a fellow Substack author, The Jewish Table by Leah Koenig then getting her cookbook: Portico: Cooking and Feasting in Rome's Jewish Kitchen. It’s a fascinating part of Rome’s history that I’m glad to finally know.

(BTW, friends, I follow several great Italian Substacks including Italicus: a writer’s life in Italy, Letters from Tuscany, and Piccolo Centro.)

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Colosseum began to deteriorate. Earthquakes damaged the structure and it was abandoned as a venue, looted for its building bits, squatted in by the poor and essentially left to rot.

A restoration project began in the 1990s, but it wasn’t until Ridley Scott’s 2000 film Gladiator that tourist interest in the Colosseum spiked and with it, further changes to accommodate the hordes. The site is now one of Rome’s most popular tourist attractions, hosting millions of visitors a year and generating needed money for city coffers. Another example of the power of cultural tourism.

Kenya.

I’m off to Tanzania and Kenya next month, to fulfill a lifelong dream on going on safari, followed by some extra days in Nairobi. Among the many things I’ll visit there is Karen Blixen’s farm, located 10km from the city centre.

I had a farm in Africa at the foot of the Ngong Hills.

Better known by her pen name, Isak Dinesen, the Out of Africa author settled into a 6,000-acre farm in 1917 (which had been financed by her family) with her new husband.

First, the coffee farm failed then the marriage did (Bror von Blixen-Finecke was a relentless womanizer with no business acumen). He left, but she remained running it on her own, finding great freedom in escaping the conventions women were subjected to at the time.

But financial difficulties continued and then her lover died. Blixen eventually returned home to live with her mother. During World War II she was active helping Jews escape out of German-occupied Denmark and writing.

Blixen’s Kenyan farm was eventually broken up into 20-acre lots and sold. The actual farm house passed through several hands and was sporadically occupied until purchased in 1964 by the Danish government and given to the Kenyan government as an independence gift.

They turned it into a college of nutrition – that it is, until the 1985 movie based on Karen’s autobiography became a smash Oscar-winning international hit starring Robert Redford and Meryl Streep.

The National Museums of Kenya then decided to acquire the house and open a ‘significant cultural landmark’ museum. The suburb where it’s located is called Karen.

Out of Africa was published in 1937 and became a huge hit. Post-colonial treatment of Blixen and her work has varied. Some dismiss her as a white European aristocrat who romanticized Africa. While still others view her work in the context of the era, also considering her position as an outsider, a Dane and a woman, and her concern and respect for African nationalists.

Blixen is rumored to have been frequently considered for a Nobel Prize but never awarded it because the Nobel jury worried about favoring Scandinavian writers.

One writer who did win the Nobel Prize for Literature is Kenyan Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o whose novel about the fight for Kenyan independence, A Grain of Wheat, I’m currently reading. It’s excellent.

Thank you for joining me for this thirtieth edition of Letterbox. See you next time!

Terrific long weekend read! Have a grand time in Africa!