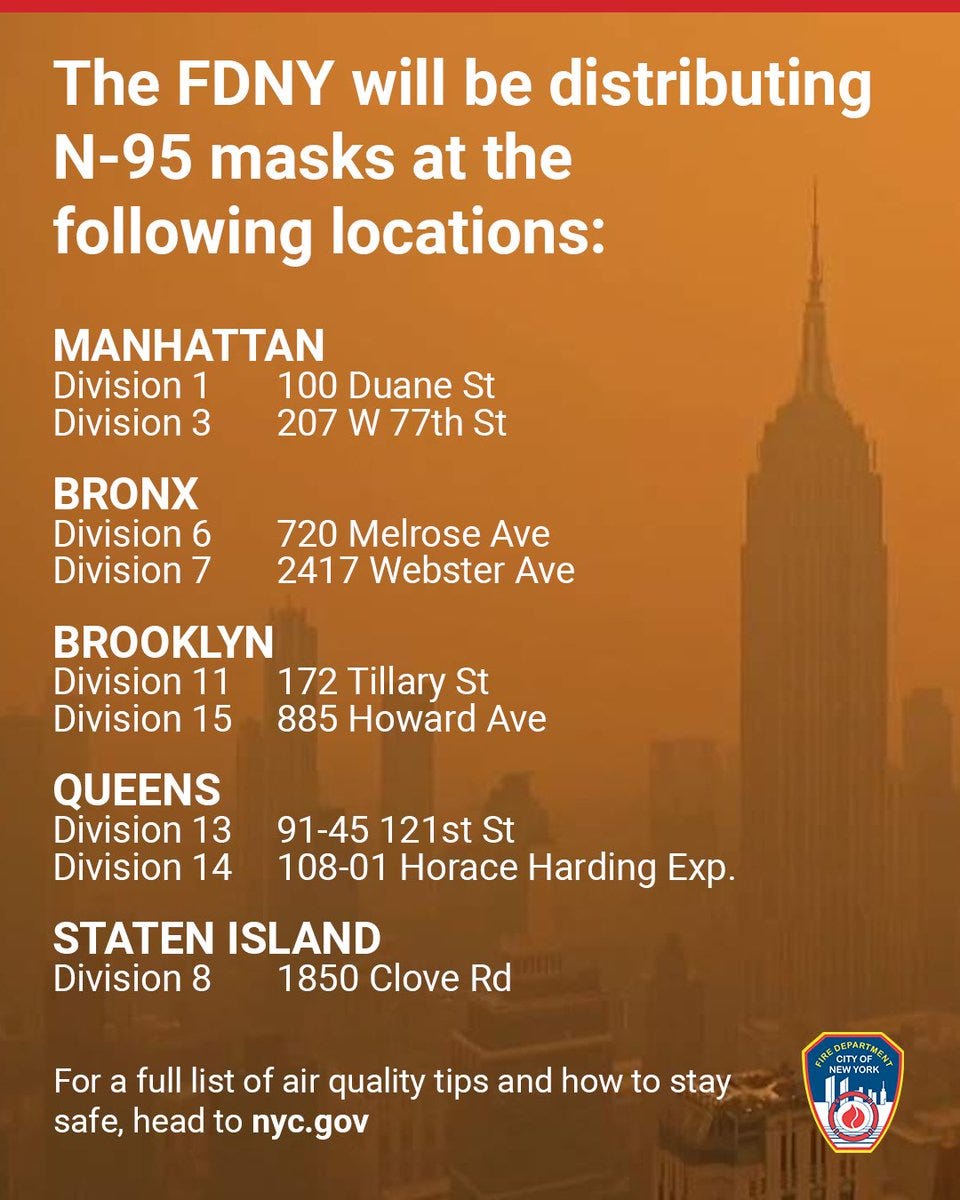

I’ve just returned from the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City. It was literally the Big Smoke: at times the air was orange and unbreathable due to forest fires burning in Québec. As one taxi driver said to me, it brought back eerie memories of the last time the air had been that bad: September 11th. And I agreed.

The Tribeca Film Festival was founde…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Letterbox: Bookish & Filmish to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.